On Sunday, Pete Buttigieg made it official. He’s running for president, because he wants “to tell a different story than ‘Make America Great Again.’”

But one way or another, his, too, will be a story of American greatness.

As an openly gay, openly Episcopalian mayor of a Rust Belt city—and a veteran who served in Afghanistan—Buttigieg is a rising star in a crowded field of Democratic contenders.

Buttigieg is making waves in part by reclaiming Christianity from the Religious Right. Not long ago, it seemed he might offer a way forward by dodging direct culture-wars engagement. When it came to Chick-fil-A, Buttigieg signaled a de-escalation strategy: “I do not approve of their politics, but I kind of approve of their chicken.” In an interview with the Washington Post, he expressed his hope that there was an opportunity “for religion to be not so much used as a cudgel but invoked as a way of calling us to higher values.” On the other hand, he hasn’t hesitated to call out conservative evangelicals for their “hypocrisy,” or to go toe-to-toe with Vice President Mike Pence. (Did he stop “believing in scripture when he started believing in Donald Trump”? How did he “allow himself to become the cheerleader for the porn star presidency?”)

In offering an alternate vision of religion and politics, Buttigieg has called for a revival of the religious left. Inspired by Catholic liberation theology and the prophetic tradition of African American Christianity, Buttigieg’s is a faith that is “about lifting up the least among us and taking care of strangers, which is another word for immigrants.” It is about “making sure that you’re focusing your effort on the poor.” And, it’s about how one conducts oneself: “Not chest thumping look-at-me-ism, but humbling yourself before others. Foot washing is one of the central images in the New Testament.” All this, he adds, is diametrically opposed to what we see in the current presidency.

With Buttigieg emerging as the new poster boy for the religious left, it’s probably a good time to reflect on the fact that the religious left hasn’t had much of a track record when it comes to electoral victories in recent decades.

On the national stage, the influence of the religious left has paled in comparison to that of the Religious Right, for a variety of reasons. The left has always lacked the financial resources and the organizational prowess of the Right—at least for the past half century. Part of this problem is an ideological one. A religion that celebrates the divestment of power is at a disadvantage when it comes to claiming political power.

The religious left faces a similar conundrum when it comes to the question of American greatness.

Buttigieg has framed his campaign as an alternative to the MAGA narrative. But it’s worth noting that Buttigieg didn’t just set himself against our current president’s rhetoric on greatness. Back in January, he offered a harsh assessment of Hillary Clinton’s 2016 campaign, and that critique, too, focused on the question of American greatness: “Donald Trump got elected because, in his twisted way, he pointed out huge troubles in our economy and our democracy.” He added, “At least he didn’t go around saying that America was already great, like Hillary did.”

This dig was too much for Clinton spokesperson Nick Merrill, who called out Buttigieg’s comments as “indefensible.” Hillary Clinton “ran on a belief in this country & the most progressive platform in modern political history. Trump ran on pessimism, racism, false promises, & vitriol. Interpret that how you want, but there are 66,000,000 people who disagree. Good luck.”

This tension between Buttigieg and the Clinton team reflects a deeper challenge that has plagued the religious left. Can a prophetic tradition rally Americans to go to the polls? Is prophetic Christianity compatible with American patriotism, and with a quest for political power?

Here, history offers some sobering answers.

During the 2016 campaign, I found myself thinking often about an earlier presidential campaign—the 1972 battle between Richard Nixon and George McGovern. As I listened to Clinton refute Trump’s startlingly dark and dour depiction of America, I wondered if her attempt to draw a sharp distinction between her vision and Trump’s wasn’t based on her own political history. Clinton, recall, had worked on the McGovern campaign back in 1972.

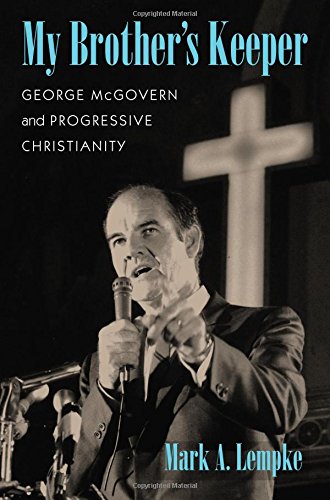

As historian Mark Lempke has written, McGovern reveals the (mis)fortunes of progressive Christianity in postwar America: “At the start of McGovern’s public career, progressive, social justice-oriented Protestant Christianity was a cornerstone of respectable civic life. Although often establishmentarian in character, it also carried a strong prophetic element that challenged the powerful and supported marginalized communities. In the 1960s and early 1970s, liberal churchmen and liberal politicians such as McGovern worked together against war and hunger and in favor of a robust, inclusive Christian humanism…”In 1972, McGovern’s progressive and prophetic Christianity countered Cold War nationalism and militarism—the defining features of the rising Religious Right. But McGovern’s campaign marked a critical turning point in progressive Christianity, revealing “the limits of prophetic action as a tool to win elections.” From that time on, progressive Christianity has struggled to inspire voters.

As Lempke writes, McGovern’s prophetic tone “may have been acceptable in a conscientious senator,” but “it was problematic in a presidential candidate who was expected to reassure rather than remonstrate.” Here Martin Marty offers a useful distinction between a priestly civil religion, which “affirms a nation and its people by evoking common symbols”—something employed by Nixon and his evangelical supporters—and a prophetic civil religion, which could entail a ruthless critique of the nation, yet in the tradition of the Puritan jeremiad, this prophetic critique allowed for hope that “the nation could overcome its faults and sins,” that it could find redemption.

In 1972, Americans voted for a priestly civil religion. In Lempke’s words, McGovern’s failure pointed to “uncomfortable truths”—“prophetic action and presidential elections do not mix well; even erudite, incisive criticism of the US will seem discordant amid the pageantry and patriotism that characterizes those events.” McGovern had asked Americans to remember “the poor and the neglected,” to think of the Vietnamese victims of the war. Instead, Americans preferred to think of busing, the draft, and their own well-being. “There is a role for such remonstration in civic life, but it is probably outside of electoral politics,” Lempke concludes.

If Clinton learned the limits of prophetic civil religion from the McGovern campaign, that lesson would have been reinforced eight years later. Clinton, it should be recalled, also worked on Carter’s successful 1976 presidential campaign, when he promised to restore hope to America after the Watergate debacle. But she also watched Carter go down in humiliating defeat four years later.

The 1980 election, too, was a referendum on priestly versus prophetic civil religion. Americans were tired of Carter’s recounting of America’s problems and deepening crisis of confidence, and of his calls for sacrifice and scarcity. They wanted a leader who saw the darkness, who knew their fear, but one who promised bold (if imprecise) leadership out of that darkness and into a glorious morning, a return to a mythical American greatness.

It shouldn’t surprise us, then, that Clinton decided to paint a rosier picture of America. Yet it is important to recognize that American voters weren’t responding to Reagan’s optimism—at least not as far as present conditions were concerned. They were responding to a dire view of the present, and to a promise of change—change that would require not sacrifice, but rather the assertion of power.

The same was true of Trump’s supporters in 2016. The darker Trump’s vision became, the more he tapped into a longstanding tradition; the Religious Right had long thrived on tales of woe and national decline. And the more Trump tapped into that tradition, the more Clinton sought to appeal to voters’ better angels. In the end, the allure of a priestly civil religion, of self-affirming talk of greatness, won out.

Even if she had wanted to, Clinton wasn’t in a position to benefit from a darker vision. She was running as a Democrat seeking to follow a two-term Democratic president. Hope and change make a compelling pitch, but this rhetoric works best when one can distance oneself and one’s campaign from the current administration. Right now, Buttigieg has that going for him.

However, as a revivalist for the religious left, it will be critical for Buttigieg to craft a compelling vision for Americans who have long preferred the priestly to the prophetic civil religion—at least when it comes to electoral politics.

Fortunately for him, he wrote his Harvard thesis under the direction of Sacvan Bercovitch, a scholar whose work traced the history of American “exceptionalism” to the New England Puritans. “You can’t understand America without understanding the Puritans,” Buttigieg insisted. “In many ways, we’re still living out their legacy in ways that are good and bad.”

The task ahead of Buttigieg will be to fashion the perfect jeremiad for this historical moment—a call to national repentance and renewal, but one that appeals to myths of American greatness. Clinton tried and ultimately failed to do so. But Buttigieg won’t be facing the same obstacles. In the midst of the devastation of the Trump presidency, there is no better time for the religious left to cast a different vision of American greatness. And if the religious left can’t inspire voters in 2020, perhaps it’s time to retire talk of any revival indefinitely.

Cite

Du Mez, Kristin Kobes. “Pete Buttigieg and The Politics of American Greatness.” 18 April 2019. (First published The Anxious Bench, Patheos.com. 18 April 2019)