A disturbing new study by Marquette University sociologist Heather R. Hlavka reports how young women today have “normalized” sexual assault to the point that they are often unable to identify harassment and rape for what they are—criminal acts.

Based on an examination of forensic interviews conducted by the nonprofit Children’s Advocacy Center in connection with reported cases of sexual abuse in an “urban Midwest community” between 1995 and 2004, Hlavka uncovers disturbing trends: “Objectification, sexual harassment, and abuse appear to be part of the fabric of young women’s lives. They had few available safe spaces; girls were harassed and assaulted at parties, in school, on the playground, on buses, and in cars.” Yet these girls often failed to see themselves as victims, instead justifying male aggression as “normal.”

As one thirteen-year-old reported, “They grab you, touch your butt and try to, like, touch you in the front, and run away, but it’s okay, I mean…I never think it’s a big thing because they do it to everyone.”

Hlavka identifies a number of reasons for girls’ acceptance of male aggression, including the prevalence of “heteronormative discourses” that “consistently link female sexuality with passivity, vulnerability, and submissiveness, and male sexuality with dominance, aggression, and desire.” In a culture that too often sees male violence against women as “normal,” as simply one more case of “boys being boys,” girls have come to accept and endure male aggression because that is simply what men do, Hlavka writes. “Young women overwhelmingly depicted boys and men as natural sexual aggressors,” Hlavka explains; they “described men as unable to control their sexual desires.” Indeed, rather than blaming male perpetrators, the interviews revealed that it was not uncommon for girls to blame themselves—and other female victims—for their inability to avoid assault.

One doesn’t need any particular expertise to find Hlavka’s study alarming, on a number of levels. But as a scholar of Christianity and gender, I couldn’t help but consider the ways in which popular Christian teachings on gender and sexuality might contribute to a culture in which girls seem unable even to recognize the violence that is perpetrated against them, sometimes on a daily basis. Indeed, in Sex & the Soul, religion scholar Donna Freitas offers a revealing glimpse at how this is indeed the case for many college-age Christian women.

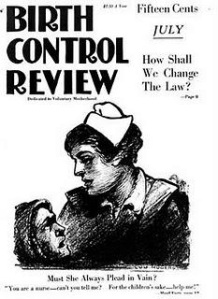

A True Love Waits ring, advertised as allowing girls to “carry your commitment to purity with you always.”

Scan the shelves of a Christian bookstore and you’re likely to find any number of books on raising godly children that parrot the “boys will be boys” mantra. When it comes to raising sons, avoiding “the wussification” of boys seems to be of greater concern to the evangelical community than addressing the sort of masculine aggression Hlavka finds all too common. And while many Christians would pay lip service to the importance of sexual restraint for men as well as for women, a virtual “purity industry” has developed in evangelical communities to celebrate, protect—and market—female purity. From a young age girls are warned by pastors, parents, teachers, youth leaders, and devotionals to dress modestly lest they arouse their testosterone-laden male peers, and taught that to “lose their purity” would leave them analogous to “dirty chocolate,” “used tape,” or “chewed up gum.”

In the face of such gendered (not to mention offensive, and, arguably, unbiblical) notions of purity, as a historian I can’t help but look back to an earlier “purity movement,” one that swept the evangelical world in the 1880s and 1890s. For a time “social purity” came to rival temperance as the leading cause for women the world over, as purity reformers busied themselves with all sorts of reform efforts; some sought to raise the age of consent, others to combat prostitution and the forced hospitalization/incarceration of women with venereal diseases, while in later years still others sought to restrict the production of “obscene” materials and resist the growing popularity of birth control. What initially united purity reformers, however, was their staunch opposition to the sexual double standard—to the Victorian Christian ideal that held women to exceptionally high standards of purity while excusing men for their regrettable (but fully expected) moral lapses.

Thus, while purity reformers sought to restrict prostitution, they adamantly opposed punishing prostitutes or shaming “fallen women.” Rather, they sought justice (and redemption) for such women while working to hold men accountable. In this way, respectable, middle-class Victorian women often found common cause with women’s rights activists of this era. Both groups agreed that women didn’t need to be protected through purity, passivity, and respectable femininity, as much as they needed to be empowered to protect themselves.

While Victorian purity reformers did not dismiss the importance of purity, they simply argued that it be stripped of its narrowly-defined sexual connotations, and that it be reinstated as an equal-opportunity virtue, prized in women and men alike. As Katharine Bushnell, one of the leading global purity activists in the late nineteenth century, wrote: purity was indeed “of great importance to women,” but women would be far better equipped to guard that virtue if they were instructed from the pulpit to be “strong, in body, mind and spirit,” rather than taught to be pure, submissive, and “feminine” (God’s Word to Women, paragraph 633).

It may seem strange to look back to a group of Victorian reformers for guidance in navigating a perilous culture for young women today, but for many American Christians, it might not be a bad place to start.

Cite:

Du Mez, Kristin Kobes. “‘Strong in Body, Mind, and Spirit’: Purity Movements and Sexual Aggression.” Historical Horizons, Calvin College History Department blog. April 25, 2014.