Summary:

The complete recording featuring Dr. Kristin Kobes Du Mez and award winning author Dr. Randal Jelks. February 16, 2019 at Schuler Books & Music, Grand Rapids, Michigan.

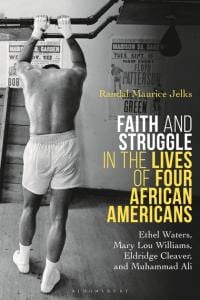

Faith and Struggle in the Lives of Four African Americans: Ethel Waters, Mary Lou Williams, Eldridge Cleaver and Muhammad Ali (2019).

Select Excerpts:

This past week I had the pleasure of sitting down with Randal Maurice Jelks, Professor of American Studies and African and African American Studies at the University of Kansas, to discuss his new book Faith and Struggle in the Lives of Four African Americans: Ethel Waters, Mary Lou Williams, Eldridge Cleaver, and Muhammad Ali(Bloomsbury Academic, 2019). The book offers a fascinating look into the religious lives of four individuals, and Jelks also weaves his own religious narrative in and out of the stories he tells.

Here is a portion of our conversation, edited for length and clarity. A full audio recording that includes a lively Q & A can be found here.

Kristin Kobes Du Mez: This is in many ways an innovative book, Randal. Can you start by telling us how this book came about?

Randal Maurice Jelks: This book came about first of all reading an article in the New York Times about radical women, by Margo Jefferson. And the paragraph that struck me most was on Ethel Waters—that Ethel Waters was a “notorious lesbian.” And I thought, I’ve got to do an article on this. I’ve got to go figure out, what was the relationship between the Graham crusade that Ethel Waters sang at at the end of her life? And then I began to think about other people’s lives that I saw, and how religion was a part of it, and how did they handle it?

Everybody writes about African-Americans for external relationships, but what about the inner self that motivates people? That’s what I that I wanted to get at. You don’t think about yourself in terms of categories, you transcend those categories.

KDM: You make the argument that the inner lives of black people are just as important to explore as the histories of human rights protests and political activism. And when you start looking at those in our lives, they don’t fit into any category.

RMJ: That’s right. Nothing is neat. I use the word heterodox for a lot of things because people’s lives are opaque, and I use that term as well. And the opacity is a part of the religious experience. People are really opaque. We don’t know all that motivates them, and I wanted to lift that up.

KDM: As I was reading this book to it occurred to me that this is black history and it’s American religious history. Did you feel like you were moving back and forth between two rather distinct conversations? When you look at these four stories, one wonders how you could talk about one without talking about the other; but how do you see the state of the fields right now, and the conversation?

RMJ: Well, I primarily teach at a state university now and I primarily teach in a secular department, and my students don’t know enough about religion. I’m always pulling out my hair, saying you really—you don’t have to believe, but you do have to understand the terms under which people engage their lives, and religious terms of which a majority of Americans still define themselves. And so it’s also a critique of the field. Like people don’t always think of themselves as determined by social class. Fannie Lou Hamer said, when she got up to fight for civil rights, Jesus told me that I had to fight this. And all these young activists, “Well, Miss Hamer, Jesus – what’s Jesus got to do with it?” And then they learn…Jesus told her to get up and be a civil rights fighter. That’s a different world. And that’s where they intersect. And people often forget that people’s lives intersect in ways so that you get up one morning, and you say, you know, I’m a sharecropper. I’m a poor woman–the worst of the categories–and Jesus told me to get up and do battle… So she had a deep sense of purpose.

It’s like Muhammad Ali. I got so frustrated. Everybody talks about Ali for being a Vietnam dissenter, about dissenting from the war, but he’s really dissenting as a religious thing–and it troubles the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court does not want to say anything about the Nation of Islam because they don’t know what to do with this religious group that has a cosmology that in fact would say they’re the devil, right?

He’s really standing on principle, his religious principle. He says, you know, my God tells me these people didn’t do anything to me. I don’t belong there fighting.

KDM: What was your most interesting or unexpected discovery in the archives?

RMJ: A novel by Eldridge Cleaver that he wrote—before he wrote Soul on Ice—about two men in love and in prison. And it had theological references and so forth.

And all of the exchanges between Mary Lou Williams and one of her priests—they were all quite moving…. And of course Ethel Waters between her and her secretary.

KDM: What was the hardest thing about this book for you?

RMJ: The hardest thing about writing this book was thinking back to how I was as a young person, thinking about my days in Ann Arbor, my confusion. You know, you get older and you’re like, “Why was I worried about that?” But in my deep search, reading materials, thinking about my own faith struggles at that time…

I first heard Mary Lou Williams—and I tell this in the book—I walked into a record store. My favorite record store then was called School Kids Records in Ann Arbor, and it was the hippest record store in the city. You know, I know people don’t buy albums–some kids in Lawrence still buy vinyl, but not at like they used to. And they would play jazz. It was jazz or punk, early punk. And they had this pianist on, and it’s this woman, Mary Lou Williams, and I had no clue who she was and then I came back there…So, the memories about when I was a young person full of confusion and trying to be…to think radically, even think Christianly at times, more so than I think now. But I was trying to think about all those things, and they brought back a lot of memories for me.

KDM: I loved how you weave your own narrative into this story, and your own religious history doesn’t fit into neat boxes either, really.

RMJ: Oh, well, you know, I tell people I grew up in the segregated world.

And I know Christian Reformed people—I’m making a joke about y’all. You think you’re the only ones that grow up in a very small world. Well, I grew up a black Lutheran and there were five black Lutheran churches in New Orleans. Every black Lutheran looked like me so much so that I thought Martin Luther King was the founder of our church ’til my mother said to me, “No, this is Martin Luther.”

In the Missouri Synod you get Luther’s Smaller Catechism with your first reader, you know, “See Dick run, run, run, run,” and “You’re nothing but a worm.” Right? You’ve got both of those right next to each other. So you’re learning now, okay, “See Dick run” and “I’m a worm.”

It wasn’t until I think 1966 that the Missouri Synod tried to start having cross-fellowship. And we had a kid’s day or something, and I came back and said, “Mom where did all these white people come from?” Because I didn’t think they were Lutheran.

KDM: You spent a good chunk of your career at Calvin College, and we talk a lot about faith and scholarship at Calvin. How essential was your own religious journey to writing this book? Could this book have been written without that faith perspective of the author?

RMJ: Well, not in the way it was done. I thought that it was very important that I share–I mean everybody on campus knows I’m Presbyterian clergy–and I also wanted to share with my other colleagues that religious people are not crazy. That it’s a tendency that that they look at only hyper-evangelicals on campus protesting. Religious people aren’t crazy. Lots of faculty people feel embarrassed about being religious. And I’m like, well, you know, this is what you get. And so I just wanted to express that in a way that I thought was constructive.

But I also really want to talk to African Americans because there is a pluralism within our community. Thirty-five percent of Muslims in the United States are black Americans. We don’t think about that. What drove me crazy at Calvin was talking about the Christian perspective. There are multiple ones, and…you’re sort of living in the middle of Corinth with a lot of different faiths and talking to people with respect, and mostly love. That’s what I was trying to get at as well.

KDM: Who do you most want to read this book? And what do you most want them to take away from it?

RMJ: When I wrote the book, I thought about African Americans. I really did, because there is such a rich discussion that goes on in every beauty shop, every barber shop.…

It was reading Gene Genovese—it’s an old book called Roll, Jordan, Roll: The World the Slaves Made. And Gene is writing about all these slaves having theological discussions. But he doesn’t take it up. But he should have.

They were actually arguing about being Methodists or Baptists. And that was real, because, you know, my grandparents were Baptist—my grandmother who I was reared with was born in 1906. She was baptized in the Mississippi River in 1918 by Reverend Sweet….And that was very important for her…. What does this Baptist stuff mean for her life? Those were meaningful things for her life.

So meaningful…I got smacked on the side of the head when I said, “Well Granny, when you got baptized, did the doves come out?” Because she said she got baptized just like Jesus. I was like, all right. [laughter] But I realized quickly on that for my grandparents those things were meaningful. And those institutions had meaningful language for them. And the Methodists have meaningful language for other people.

And we should take the people’s language is seriously when people talk about the Holy Ghost that they used to say. So I wanted to take those terms and those faith terms as respectfully as I would want others to take the terms that that that I might use. You know, if I say providential, you know–God’s good Providence, this occurred–then we should take it a little seriously.

And I thought I’m kind of in a perfect bridge spot, right between the life of the academy and a life of ordinary [folks]. I’m the only one in my department who’s ever buried the dead. So, people’s symbols you have to take very seriously. And everything can’t be class consciousness. Yes, religious people can be–on all sides–can be a little bit nuts and vote against their interests at times, but they also are moved to do extraordinary things.

So, for all the things that I know about evangelicals, I always tell my cocktail liberals that my evangelical friends actually go out in in the middle of the Ebola crisis and do nursing and working and y’all are just talking about it. So, you know, lay off. [laughter] So there’s both sides to that.

ISBN: 9781350074620

ISBN-10: 1350074624

Publisher: Bloomsbury Academic

Publication Date: January 10th, 2019

Pages: 208

Language: English